Mapping a Journey

Sarah Chase is a Canadian independent dancer and choreographer and has established her reputation as a solo dance artist, presenting her works on tour across Canada and Europe. Sarah has choreographed and directed unmoored, which Peggy will be performing as part of Map by Years February 21-25, 2018 at The Theatre Centre.

1. How did you and Peggy meet?

I first met Peggy when I was a student at the School of Toronto Dance Theatre in 1988.

2. Tell us about your first experience dancing for Peggy.

Her teaching and presence were a revelation. She was dancing in New York at the time, and was our guest teacher for a week. She blew our minds: this striking, brilliant, tall, totally articulate woman, both in the way she moved and in the way she spoke. Forthright, full of light, with the passion, vibrancy and clarity of all that she had been inspired by in dancing in New York and internationally. She had been dancing for Lar Lubovitch, Mark Morris, and had been developing new ways of considering movement and kinesthetic anatomy with Irene Dowd. She made me feel like dance language was an illuminated manuscript sending paths of light through space. In fact she spoke this way about movement, extending imagery beyond the body into the architecture of the room, of the studio. We were invited to dance across the studio like flocks of birds tipping and tilting as we arced through our paths, or to consider that we were leaving light trails in the volume of the room and that by the time we had finished our dance we had left a kind of lit up architecture floating and resonating in time.

And these weren't just words, she was able to totally embody the tasks and imagery she offered us, firing our mirror neurons to new fresh experiences.

There was also the feeling in her dancing of having grown up in the open generous spaces of the high Canadian prairie, this understanding of big swathes of landscape and open sky were indelibly understood and carried by her.

I felt like a door opened for me. She responded to my dancing with excitement, affirmation, and acceptance. I had that intense and wonderful sensation of really being seen, and amazingly she offered to help me design a path of further study in NYC after graduation.

I would continue to study with Peggy whenever I could, in workshops and intensives in Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver. And I did end up in NYC for a year where I was able to study with some of Peggy's incredible teachers and influences like Irene Dowd and Christine Wright, and to be immersed in the company of the dedicated extraordinary people dancing in the major companies there at the end of the 80s.

In preparing for further creation on unmoored I was reading Rumi and Hafiz as translated by Daniel Ladinsky. In his introduction he writes: "I was recently asked if I could explain the Rumi phenomenon in the Western world in just one line. I thought for a few moments, then replied, "Well maybe but could I quote Hafiz? The line was 'The wing comes alive in his presence/ I think that is it, something of the answer. The wing, the soul, the heart, comes alive in the presence of a real teacher...'"

Sarah in Garland, 1997. Choreographed by Peggy. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann

3. In 2003/04, you and Peggy created The Disappearance of Right and Left. What inspired you to return to develop this follow-up piece now?

When Peggy and I worked on The Disappearance of Right and Left it involved unearthing many compelling stories from Peggy's life and looking at their relationships with each other. There is always a major process of elimination, looking for stories that somehow resonate together and create a greater whole. In The Disappearance, the stories chosen all seemed to illustrate times when perception was turned sideways and changed or opened.

Hornby Island

Peggy on Hornby Island, 2017, working on unmoored

Often, when creating work it helps immensely to have some distance on past events and to know that it is safe to share the stories we are working with. We both knew that at the time of creating The Disappearance that Peggy was right in the middle of some excruciating life choices and fully immersed in taking care of Ahmed [Peggy's late husband]. We thought that one day we would return to this story, so central to her life, and around two years ago, it felt like the right time to begin.

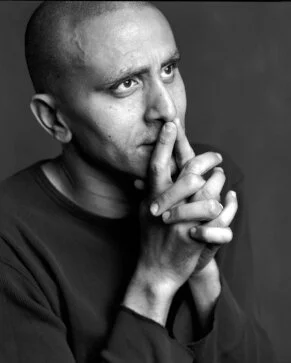

It was an event when Ahmed would play for our classes when I was a student at STDT. He often sang while he played his array of instruments. I couldn't believe that one person could bring such a landscape of sound to the studio. So, I knew him before I met Peggy. And I was thrilled when these two people I loved got married to each other. At first, Peggy and Ahmed did some touring together and I would stay with Ahmed's daughter Shireefa, as a guardian; later on I would stay with Ahmed to help out when Peggy was away.

AHMED. Photo by v. tony hauser

Sarah, Ahmed, and Tonto, 1994

One thing that was a great pleasure about Peggy's teaching was her interaction with the musicians who played for class. She was deeply appreciative and aware of the choices they were making and her exercises were built around their musicality and sometimes involved unusual time signatures. There was a feeling of complete engagement both musically and physically. When Peggy made the solo, Garland, for me in 1997, it was an incredible experience to dance live to Arraymusic: four musicians playing violin, piano, vibraphone and tom toms, who shared the stage space with me. Over and again, Peggy has chosen to bring the musician right into the centre of her performances. Her solos transformed to an intimate duet.

4. Your career has been grounded in combining storytelling and dance, how does this inform your art-making process?

I think we are all in the middle of a mystery, and each of us experiences in our lives some kind of intricate predicament. In hearing other people's stories I often feel a deep sense of relief to know that I am not alone in feeling bewildered or overwhelmed by experiencing love and loss, which is inevitable in any life well lived. When I make work I am hoping that by arranging personal stories in a careful constellation, they become universal. A kind of poetic logic and rigour takes place, making sure that not more is said than needs to be said. I am always interested in specific details.

In the meantime I am creating movement patterns and loops that can speak emotional subtext or say what can't be spoken. These danced patterns also serve as a grounding task that keeps the performer in the moment and therefore safe to speak about personal emotional experiences.

To see unmoored, get your tickets to Map by Years, here.